- Home

- Richard T. ; Ryan

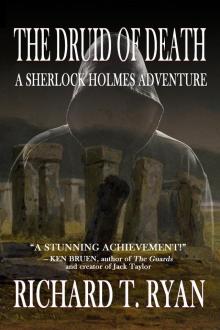

The Druid of Death - a Sherlock Holmes Adventure

The Druid of Death - a Sherlock Holmes Adventure Read online

The Druid of Death:A Sherlock Holmes Adventure

by Richard T. Ryan

2018 digital version converted and published by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

First edition published in 2018

Copyright © 2018 Richard T Ryan

The right of Richard T Ryan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998.

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without express prior written permission.

No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted except with express prior written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damage.

Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this book, as of the date of publication, nothing herein should be construed as giving advice. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and not of MX Publishing.

MX Publishing

335 Princess Park Manor, Royal Drive,

London, N11 3GX

www.mxpublishing.com

Cover design by Brian Belanger.

As always, this book is dedicated to my wife, Grace, who not only does the impossible on a daily basis but puts up with it as well.

And to my children, Dr. Kate Ryan-Smith and Michael, as well as my son-in-law, Daniel. Each, in his or her own way, is a source of inspiration to me.

Finally, this book is dedicated to the memory of my parents.

Introduction

Those who have read either one of the previous stories that have appeared under my name are familiar with the origins of the manuscripts. While on a golfing holiday in Scotland, I attended an estate sale where I emerged victorious, after a rather spirited bidding war, as the owner of a locked box.

Upon forcing it open, I discovered a second box inside the first. Equally surprising was the fact that stenciled on the lid of the second box was the name “John H. Watson.” Indeed, it was the famed tin dispatch box of Sherlock Holmes’ friend and companion. Moreover, it was filled with manuscripts that had failed to see the light of day for various reasons during the great sleuth’s lifetime.

I believe that “The Vatican Cameos” was held back because of the possible political fallout it posed to a newly unified Italy as well as the potential embarrassment its release might have caused the papacy.

“The Stone of Destiny” was never published, I assume, because of the political tension that existed between England and Ireland at the time. I suppose a secondary reason for keeping it hidden might have been the fact that its release might have placed Holmes in a rather precarious position with the powers that be.

With this book, which Watson had titled “The Druid of Death,” there can be no doubt as to why the adventure was kept secret. Attached to the folder that contained the manuscript was a letter in the good doctor’s handwriting that explained his reticence in making the public aware of the facts.

Having read the entire tale, I find myself in agreement with Watson’s assessment; however, that is a judgment that each reader must make for himself. To that end, I have provided a copy of the doctor’s letter, and I leave it the individual reader to decide whether to press on and read the tale or to heed the wishes of Holmes.

As I said, I find myself siding with the doctor, and my decision is rendered with a genuine tenderness for Holmes and the honest belief that at least in this one instance, Holmes’ vanity would deprive readers of an otherwise excellent adventure that I believe shows him at the absolute top of his game.

I think, had the Great Detective enjoyed the advantage of hindsight that we enjoy as well as the objectivity that we can bring to bear on this tale, he might have been persuaded to change his mind.

At any rate, here is the tale, preceded by Doctor Watson’s missive. I hope you enjoy both, but I will certainly understand, if after perusing the letter, you should decide not to read the book.

Richard T. Ryan

Preface

10 June, 1910

More than a decade has passed since the strange and tragic events that gripped the nation in 1899. In his long and storied career, I believe that these events constituted, without a doubt, one of the more unusual cases in which Sherlock Holmes ever became involved.

Much of the story has been withheld due to a certain sense of propriety and the abhorrence that both Holmes and I share with regard to scandal.

However, the real reason that the case was never published is quite simply because Holmes forbade it. In retrospect, I can understand his feelings on that matter. I have often written of my friend’s vanity, perhaps his greatest weakness.

This case was one in which Holmes labored mightily, but with so few clues at his disposal, it was one in which he ultimately felt that he had not covered himself in glory. In fact, his exertions were such that at one point I even toyed with the idea of titling the work Holmes Agonisties.

Although I vehemently disagreed with him then (and I still do), I was not about to let the publication of such events drive a wedge between us. I valued Holmes’ friendship far more than the few pounds I might have made from their publication.

Still, I think this adventure demonstrates all the better qualities that make up Sherlock Holmes - tenacity, ingenuity, brilliance and, dare I say it, compassion - and that they can be seen shining brightly through the otherwise sordid events.

And so, as always, the choice falls to someone other than I to make the decision as to the disposition of this work.

Those who have admired Holmes may want to honor his wish and perhaps re-read one of my other efforts. To quote Geoffrey Chaucer, you may feel free to “Turne over the leef and chese another tale.”

However, I believe that those who choose that course will deprive themselves of as fine an exhibition of deductive prowess and wide-ranging knowledge as it has ever been my privilege to witness and chronicle.

Sincerely yours,

John H. Watson

“Noli tubare circulos meos!”

(Do not disturb my circles!)

Some believe these to be the last words of the Greek scientist and thinker, Archimedes

Chapter 1 - London, 1899

After a rather unremarkable winter, marked by a conspicuous absence of storms, during which Holmes and I were kept exceedingly busy, spring appeared to arrive early in 1899. By the second week of March, it had grown unseasonably warm, and I was beginning to think that crime had decided to take a holiday to celebrate the end of winter.

On Monday, the 20th, spring officially arrived without any undue fanfare. The day was rather mild and sunny, but otherwise, like the winter that had preceded it, totally without distinction. I say that because I remember distinctly that it passed without incident. In retrospect, I now realize that it truly was the calm before the storm.

The next morning, I awoke to discover Holmes had gone out early. When she brought my breakfast, Mrs. Hudson informed me that Inspector Lestrade had arrived at about seven o’clock and awakened her and Holmes in that order.

With nothing else to occupy my time and no word from my friend, I spent the day seeing a few patients and catching up on my correspondence. I ate a solitary dinner as Holmes had yet to return. After my meal, I visited my club, and when I returned to Baker Street, it was to an empty sitting room.

I was somewhat surprised - although not totally - at having n

o communication from Holmes.

I was just preparing to douse the lights and turn in when I heard my friend’s familiar tread on the stairs. As he entered, I could tell by the dour expression on his face that something was terribly amiss. “What’s wrong, Holmes?”

“It’s a very bad business, Watson,” he said rather sternly, shaking his head. “Very bad, indeed!”

“Where have you been all day, and what on Earth has happened?”

He replied, “I have spent the entire morning traveling and the better part of the afternoon at Stonehenge and have only just returned from Salisbury.”

“What in heaven’s name were you doing there?”

“Lestrade arrived shortly after the sun had risen this morning and had Mrs. Hudson rouse me from my bed. He then informed me that a ritual murder of some sort had been reported at Stonehenge. Since the local constabulary had requested that Scotland Yard look into the matter, he asked if I would be kind enough to accompany him.”

“And what did you discover?”

“We arrived about midday and made our way to the site, which was now ringed with officers. On one of the smaller stones that might be said to resemble an altar, lay the naked body of a young woman. When I arrived, she had been covered by a sheet. If I were to guess, I would say that she was of average height, perhaps 140 pounds, with well-developed leg muscles and a head of ash blonde hair. A glance revealed that she had died from a single stab wound to the heart, after which she had been eviscerated.

“Her organs had been carefully arranged around the body, and her own blood had been used to paint a number of symbols on various parts of her body. Above her head and at both her sides were branches that had been cut from a yew tree. They had obviously been positioned with care.”

“My word, Holmes!”

“Yes, Watson. There is an evil here that I have scarce encountered in my career.”

“It does recall the Whitechapel murders, does it not?”

“In some respects, this crime and those are quite similar. What terrifies me is that I can discern a similar malevolence here as when I looked into those murders.”

“What’s to be done?”

“The police are still trying to ascertain the identity of the unfortunate woman. I fear though that is the least promising avenue of inquiry. While her past may shed some light upon her murder, I am more inclined to think that the symbols on her body offer a far more promising line of investigation.”

“Do you have any idea what the images might signify?”

“If I were pressed, I should say they were druidic symbols.”

“Why druidic?” I inquired.

“Because she was murdered on the vernal equinox, a day regarded as holy by both the ancient druids as well as their contemporary counterparts.”

“My word,” I exclaimed, “that certainly would give one pause. And are there modern druids?” I asked.

“Indeed,” replied Holmes. “Right here in London, we have a chapter of the Ancient Order of Druids, a group that has been among us since the late 18th century.”

“Ancient Irish priests in modern-day London! You can’t be serious!” I exclaimed. “I thought that the Ancient Order of Druids was more a social club than a religious body.”

“Well, that’s what it appears to have evolved into over the decades since its founding, but we must consider the possibility of a coven of renegade members - perhaps entire lodges - discerning a certain wisdom in their pagan forbears and clamoring for a return to ‘the old ways’.”

“My word, Holmes!” I exclaimed. “You can’t be serious.

“I have the mutilated body of a young woman crying for justice,” said my friend. “I have never been more serious.

“These contemporary groups that exist in London were no doubt influenced - and inspired if you will - by two Welsh organizations, the Druid Society, which was based on Angelesey, or Ynys Môn, a small island off northwest coast of Wales; and the Society of the Druids of Cardigan, both of which were established sometime in the mid-18th century. I cannot vouch for the historical accuracy of either of those groups, but I can say with absolute certainty that their names and a portion of their iconography are based upon what was then believed about the ancient druids.”

“And what exactly do we know of druids?” I ventured.

“Give me a moment,” said Holmes, who then ventured into his bedroom and returned with a copy of Julius Caesar’s “Gallic Wars” and another tome titled “The Origin of Tree Worship.”

“You are just full of surprises, Holmes,” I remarked. “‘The ‘Gallic Wars’ and ‘The Origin of Tree Worship.’ I’ll be damned.”

“I believe you’ve seen the latter previously,” said Holmes who then ignored me as he thumbed through the first book, “Ah, here it is,” he remarked. “Allow me to paraphrase if you would:

“Throughout Gaul there are two classes of persons of definite account and dignity. One of these is the druids, and the other is the knights. The druids often concerned themselves with questions with the worship practices and the due performances of sacrifices, both public and private, as well as the interpretation of ritual questions.”

“Sacrifices,” I exclaimed, “both public and private. Given your prologue, am I to conclude that their customs included human sacrifices?”

Holmes continued, “Caesar goes on to say that the druids offered human sacrifices, primarily for those who were gravely sick or in danger of death in battle. Huge wickerwork images were filled with living men and then burned; although the druids preferred to sacrifice criminals, they would choose innocent victims if necessary.

“I suspect, from what little I know of their religion at present and what Caesar tells us, that human sacrifices were a minor aspect of their belief system, and perhaps not even a core tenant.”

“There was no wicker man at Stonehenge, was there?”

“No,” my friend replied, “which makes me think that if this is a druidic sacrifice, it is, at best, tangentially related to their religious beliefs. No, Watson, I believe this is something else entirely, but for the life of me, I’d be hard-pressed to tell you what it is.”

After a long pause, he added, “You have to realize, old friend, that the ancient Celts looked upon death as merely a passing of sorts. As I understand it, some druids believed in reincarnation and that the soul would be reborn in this world - perhaps as another person, perhaps as a rock or a tree.”

“What utter poppycock!”

Holding up his copy of “The Origin of Tree Worship,” Holmes remarked, “I’m not certain we should dismiss anyone’s belief system that simply. After all, consider the basis of Christianity. They believe that their god assumed the guise of a man, lived among us and then was crucified so that the gates of heaven might be opened to man once again. I’ve found it’s always best never to reject something out of hand just because we neither understand nor agree with it.”

I found it hard to argue with my friend’s sentiment on that particular point, so I opted to remain silent.

“I think it is imperative as we move forward that we keep an open mind. After all, as a medical man, you know that germs and bacteria, invisible to the naked eye, are responsible for infections and various diseases. You cannot see those organisms, yet you know that they exist.”

“But that is a matter of science,” I argued.

“Indeed,” replied my friend, but arriving at your science must have required a giant leap of faith on someone’s part in the past.”

Knowing that to debate the point was fruitless, I simply said, “Agreed.” I was more than happy to concede a small victory to my friend after the day he must have endured.

“What is your next move?” I asked.

“They are bringing the woman’s body to London. In fact, it may have already arrived. I was hoping that you might accompany me to the morgue tomorrow and examine it with a practiced eye. I am afraid that I may have missed something amid all the hubbub at Stonehenge.”

<

br /> “I’d be happy to lend you whatever assistance I can.”

“Splendid,” said Holmes. “And now, perhaps a pipe before bed while you fill me in on your day?”

As I recounted the details of my rather mundane day, I could see that Holmes was only half listening. I knew his mind was miles away on the plains north of Salisbury, trying to make sense of what appeared to be on the surface a totally senseless and savage murder.

Chapter 2

The next morning, I awoke at nine and when I entered the sitting room, I found Holmes exactly where I expected him to be, sitting in his chair, poring over the morning papers.

“For a change, they seem to have all the facts correct, and as I suspected, there is nothing in the different reports of which I wasn’t already aware.”

Throwing the papers to the floor, Holmes stepped to the door and bellowed, “Mrs. Hudson, we are ready for breakfast.”

A few minutes later, our landlady entered carrying a tray that bore two covered plates. “There’s no need to yell, Mr. Holmes. I’m only downstairs. You could just ring the bell, you know.”

“I do apologize, Mrs. Hudson, but I have a great deal on my mind, and I fear that you and Watson will bear the brunt of my frustration until I can make some headway with this case.”

“No need to apologize, Holmes. We understand the situation and stand ready to assist you in any way we can, don’t we, Mrs. Hudson?”

Looking at me and then Holmes, she nodded, saying, “The doctor speaks for both of us, Mr. Holmes.”

After a rather awkward pause, Holmes looked at her and said, “I presume you have made toast as well?”

As she left, Holmes looked at me and muttered simply, “Thank you, Watson.”

After we had finished our breakfast, we hailed a hansom cab and made our way to the Royal London Hospital, a place with which Holmes and I were all too familiar. We had visited the institution on Whitechapel Road a decade earlier, when the Ripper roamed free, terrorizing the inhabitants of the institution’s environs.

The Druid of Death - a Sherlock Holmes Adventure

The Druid of Death - a Sherlock Holmes Adventure